Recently Ontarians woke up to this reassuring Amber Alert.

The alert was sent in error—there was no nuclear incident at Pickering, lethal fallout is not even now creeping across the Province, and anyone who went full-bore Panic in the Year Zero is no doubt even now writing apology notes to their surviving neighbours—but it did serve one useful purpose, which was to remind me of that long-ago golden age of nuclear reactor mishap stories.

It may seem a little odd that people were entranced by the possibility of death by nuclear reactor calamity when we are all perfectly comfortable with millions of deaths per year due to fossil fuel pollution, not to mention events like the New London School explosion, the Aberfan disaster, and the Lac-Mégantic rail disaster. The extraordinary catches the imagination when the commonplace doesn’t. Thus far, real-life nuclear disasters have been unusual. It’s the same reason people write novels about giant meteors crashing into the Earth and not about the legions of people who die every year in traffic mishaps. It’s the same reason that murders in affluent or suburban neighborhoods get a lot more attention from the Canadian Press than the disturbing drumbeat of equally gruesome homicides along the Highway of Tears.

Here are five classic tales of Atomic-Powered DOOOM to read as we nervously scan the skies (whilst blithely ignoring the air pollution).

“Blowups Happen” is set in Robert A. Heinlein’s Future History. Rising demand for energy justifies the construction of a cutting-edge nuclear reactor. There is little leeway between normal operation and atomic explodageddon, which puts a lot of pressure on the power plant’s operators. A work environment that requires flawless performances—lest a moment’s inattention blow a state off the map—results in significant mental health challenges for the workforce. How to keep the workers focused on their task without breaking them in the process?

This story dates from what we might think of as the Folsom point era of nuclear energy… No, wait, that’s unfair to Folsom points, which are sophisticated hi-tech, really. This was the era when the atomic version of fire-hardened spear points was still on the drawing board. Hence Heinlein can be forgiven for getting essentially every detail about nuclear power wrong. What wasn’t clear to me was how a power plant composed of pure atomic explodium got licensed in the first place. Perhaps it was because this nonchalant attitude towards safety infuses the whole of the Future History. Just ask Rhysling.

***

I don’t know if Lester del Rey’s Nerves was influenced by “Blowups Happen”. Like the Heinlein story, the tale is set at an atomic facility whose initial licensing implies an astonishing lack of due diligence by public safety officials. Unlike in the Heinlein story, our heroes do not manage to keep all their saucers in the air. Told from the point of view of the facility’s physician, del Rey depicts a gradually escalating crisis. Early signs point to a minor, easily contained fumble. Events spiral out of control. The entire region, perhaps the entire planet is in danger.

Novels like this almost never include the irate public hearings that no doubt follow the mishap, so the reader is denied the hilarity of the responsible bureaucrat trying to explain why the facility was ever built in the first place.

Heinlein at least tried to be plausible; del Rey just invented things on the fly, whenever the plot demanded. Nevertheless, the pacing is well done and the result engaging, as long as you can ignore the fact that the science is pure quill nonsense.

***

In The Prometheus Crisis by Frank M. Robinson and Thomas Scortia, twenty-dollar-a-barrel oil forces America to use the same know-how that gave the world the Mark 14 torpedo and the Ford Pinto.The twelve-thousand-megawatt Cardenas Bay Nuclear Facility— the Prometheus Project—will be the world’s largest nuclear power complex. True, the project has been plagued with endless minor problems, but only General Manager Parks is worried. All his bosses take comfort from the fact that since all the problems have been manageable thus far, all future problems will be as well.

It’s not a spoiler to say that things do not go entirely well. For one thing, the text makes it clear Congress is looking for someone to blame for the Cardenas Bay Incident. For another, the cover has a mushroom cloud on it.

While American light-water reactors have failed to render the West Coast uninhabitable, the novel does paint a very accurate picture of a pathological process found in many real-world disasters, normalization of deviance. Standard safety procedures are ignored, risky shortcuts are taken. When nothing bad happens, the people concerned convince themselves that nothing bad will happen. This works until KABOOM.

***

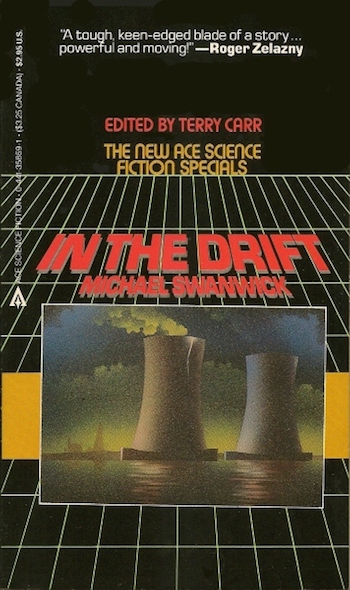

The U.S. has had nuclear power mishaps from time to time but thus far none of them have forced the evacuation of large urban regions. Science fiction can rewrite history to better suit narrative demands. Thus, in Michael Swanwick’s skillfully crafted In the Drift, the Three Mile Island incident spiraled out of control, raining radioactive debris over the Eastern seaboard. The consequences are explored over several generations. This work was striking enough to earn its author a spot in Terry Carr’s justly well-regarded third Ace Special series.

***

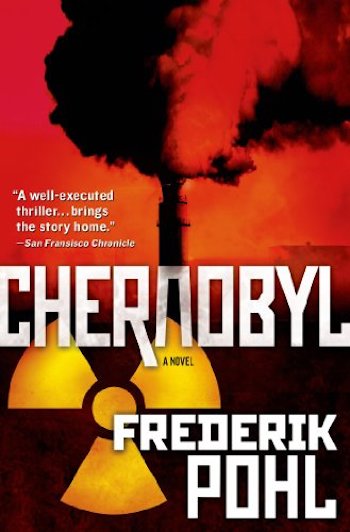

Whereas Americans have been laggard in providing the world with spectacular nuclear power disasters, Russia has done hero’s work in this field. Fred Pohl’s Chernobyl is a fictionalized account of the events leading up to and following events on Saturday 26 April 1986, at the No. 4 nuclear reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Thanks in large part to our old friend “normalization of deviance” and a political system that didn’t encourage whistleblowers, the Soviets staged the closest real-life re-enactment of The Prometheus Crisis that we’ve seen thus far. (Second place goes to Fukushima, of course, with the UK Windscale taking the bronze.) Pohl, never a fan of fission reactors, provides an enthralling account of the disaster, which might even be somewhat related to what actually happened.

***

In real life, of course, the odds do not favour dying due to a reactor mishap, any more than they do getting smushed by a space rock, irradiated by a supernova, or buried under volcanic lava. But that doesn’t mean we cannot enjoy reading about unlikely disasters, so feel free to suggest similar works below.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assAlsted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He was a finalist for the 2019 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, and is surprisingly flammable.